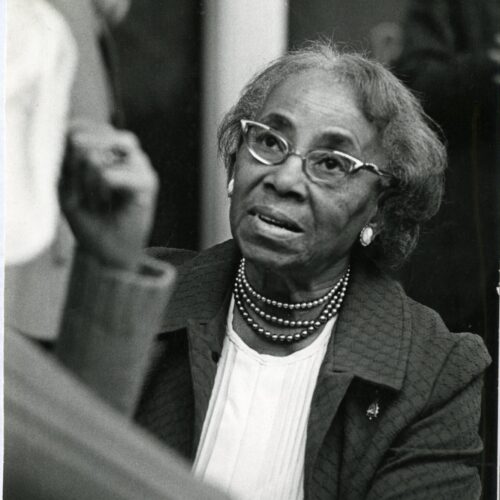

Biography

Early Life

Septima Clark grew up in Charleston, South Carolina, as the second of eight children born to devout Methodist parents. The value of education was emphasized throughout her life and Clark was inspired by activism in religious communities from a young age.

She attended United Methodist and African Episcopal Methodist (AME) churches with her mother and sisters and was exposed to the theology of Black empowerment – which rejected white supremacy and encouraged social justice work and political action.

She earned her bachelor’s degree from Benedict College in Columbia, South Carolina, and her master’s degree from Virginia’s Hampton Institute.

She began her teaching career in rural private schools. Charleston law prohibited Black teachers from working in public schools.

Academic Activism

Clark witnessed the injustice and violence of white supremacy in the education system. This led her to organize an adult education program for Black people in the rural areas along the coast of South Carolina. She also worked with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Palmetto State Teachers’ Association and the Young Women’s Christian Association.

She developed a lifelong passion for Black literacy and liberation. This led to her being involved with numerous campaigns that expanded wage equality. She also provided professional development for teachers, called for integrated education, and helped attain legislation allowing Black teachers to work in public schools.

After declaring her NAACP membership, she was terminated from her public school position in 1954. This was because of a law prohibiting teachers from joining the NAACP. Afterward, she began teaching at the Highlander Folk School the following year.

The Citizenship Schools Education Program

Through her 30 years of innovation, leadership, activism, and teaching experience, Clark developed her Citizenship Education Program (CEP). She wrote most of the curriculum for the Citizenship Schools while at the Highlander Center. This was the model for citizenship schools at the Highlander Folk School and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. From 1957-1970, Clark led the development of more than 1,000 independent schools. The organization trained an estimated 10,000 leaders throughout the Deep South. The model led to widespread increases in literacy, employment, voter registration, and political action for Black Americans. She chose Jones Island for the first training location.

Black historian, Charles Payne points out that it was women like Septima Clark and Ella Baker who laid the foundation for the Civil Rights Movement. He writes that it was not the charismatic leaders who made the Civil Rights Movement viable or successful. He doubts that a few charismatic leaders would have been able to inspire so many people who were without legal rights and subject to oppression and violence–to actively work to change the conditions of their lives.

Septima Clark and Ella Baker both emphasized and focused on empowering everyday people.

Clark’s other notable achievements include the successful publication of both of her memoirs: Ready from Within: Septima Clark and the Civil Rights Movement and Echo in my Soul.

In 1975 she was elected to the Charleston School Board and became the first Black woman to serve in the position.

Civil Rights Movement

The extent of Clark’s activism has frequently been limited in historical narratives, mirroring the marginalization she faced from men in leadership and within her religious communities.

Throughout her life and her literature, Clark frequently advocated for Black women’s involvement in civil rights, calling attention to men-led civil rights organizations and the direct undermining of women’s importance to the Black community’s progress.

She wrote in Ready from Within, “In stories about the civil rights movement you hear mostly about the black ministers. But if you talk to the women who were there, you’ll hear another story. I think the civil rights movement would never have taken off if some women hadn’t started to speak up. A lot more are just getting to the place now where they can speak out.”

Clark’s faith provided her assurance in her activism to advance civil rights and empower Black women grassroots educators.