Biography

Early Life

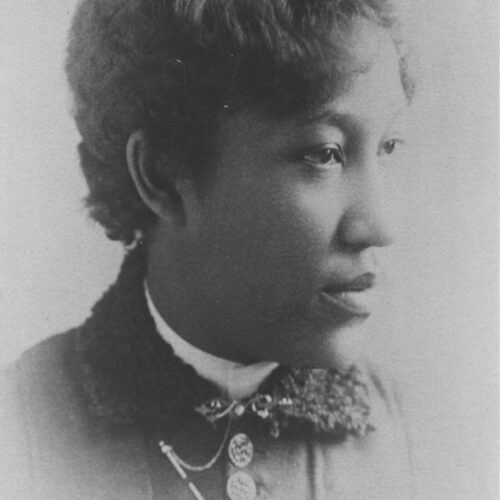

Harriette “Hattie” Gibbs Marshall was the first Black woman to graduate from Oberlin’s Conservatory of Music. She was later the founder of the Washington Conservatory of Music and School Expression, and a leader in the Baha’i faith.

She was born in 1868 in Victoria, Canada, and her parents ingrained the value of education and community service in her. Her father, Mifflin Gibbs was also involved with the San Francisco Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. He organized a Black migration to Victoria in the British Columbia province of Canada.

After a couple of decades in Victoria, the family relocated to Ohio. Following her mother Maria Gibbs, she attended Oberlin College in the 1850s. Harriet became the first Black woman to graduate from the Oberlin Conservatory of Music in 1889.

Before beginning as the appointed Director of Music in the Washington, D.C. public school system in 1902, she started the Eckstein-Norton Institute Musical Company in Cane Spring, Kentucky. A year later, she opened the famed Washington Conservatory of Music (later expanded to drama and public speaking), which was the first institution in the United States focused on educating Black youth in creative arts.

The Baha’i Faith

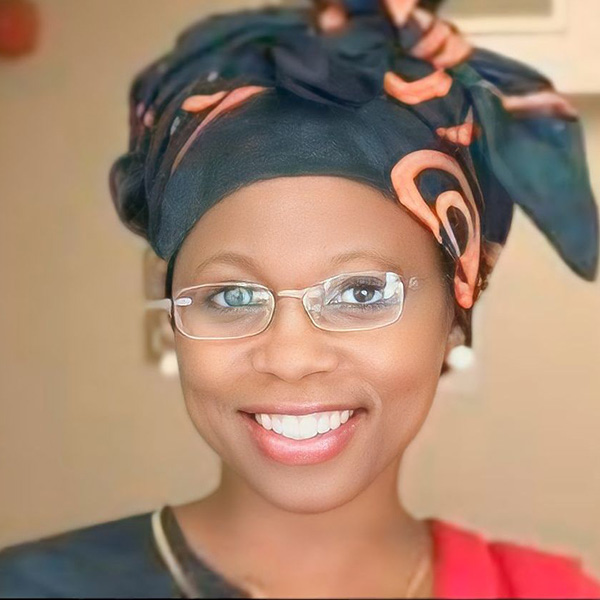

Within a decade, she married Napoleon Bonaparte Marshall and joined the Baha’i faith. The Baha’i religion began in 1893 in the U.S. But it originated in 1863 in Iran. The prophet and founder Bahaullah spread his teachings on the unity of God, religion, and mankind.

What appealed to members like Marshall, was the belief that racial justice must be achieved all over the world, and that Black people were essential to the work of creating an equal and just world.

The interracial nature of the faith proved troublesome amongst strict segregation and discriminatory practices in the United States. So Marshall often used the Washington Conservatory to host Baha’i events.

Missionary Work

Marshall also worked as a transnational missionary to spread the Baha’i faith. She accompanied her husband on a six-year assignment in Haiti.

She successfully paved the way for other Baha’is to minister in Haiti, and her most noted achievement was the founding of the Jean Joseph Industrial School in the nation’s capital Port-au-Prince. When she returned to the United States, she shared her experiences with Black audiences, which included an appearance at Tuskegee University.

Marshall’s message aligned with the major values of the Baha’i faith. She recalled that she “endeavored to impress my hearers with the necessity of our children knowing more of the Black peoples of the world that we might mutually inspire to aid each other.”

Following her engagements, she wrote The Story of Haiti (1930), which she said was meant “to inspire especially our young people with more pride, courage, and manhood.” In the 1930s, Marshall turned her efforts back to music education at the Washington Conservatory. In 1937, she founded the National Negro Music Center to be a lasting archive of the Washington Conservatory and developed instructional curriculum about Black music.

The Washington Conservatory continued to operate decades after Marshall’s death in 1941. Her educational legacy and contributions to the Baha’i faith continue to impact multicultural generations in the United States and beyond.