Biography

Early Life

Delores Williams grew up in the rural South. Her parents, Harvey Williams, Sr. and Gladys Woods, were Seventh Day Adventists. Church was a big influence and a shelter from some of the Jim Crow harshness of the South. Even as a child, Williams was aware of some of the horrors of racism. She was also aware of the strength and resilience of Black women around her who experienced both racism and sexism. She graduated from Central High School in 1950 in Louisville, Kentucky. Later she worked for several years as a reporter for the Louisville Defender, an African American newspaper.

Delores Williams became a Presbyterian after she married her husband in 1958, Robert C. Williams. He was a minister. They marched in Civil Rights marches in New York, Tennessee, and Alabama. Together they had 4 children: Rita, Celeste, Steven, and Leslie.

She earned a B.A. from the University of Louisville in 1965.

Education and Teaching

Delores Williams earned her Ph.D. in Systematic Theology at Union Theological Seminary in 1991. While there, she founded the Black Women’s Caucus.

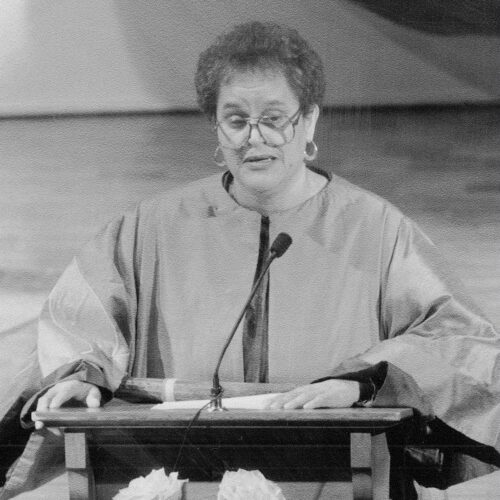

Dr. Williams was the Paul Tillich Professor of Theology and Culture and the first Black woman at Union Seminary to hold a named chair. Union honored her with the Unitas Distinguished Alumni/ae Award in 2008.

Early Articulation of Womanist Theology in Academia

Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk was one of the earliest books on Womanist Theology, published in 1993. It has been described as a critically important text by her colleagues at Union. Her books and writings laid a foundation for the academic field of Womanist Theology. Her writings have been described as poetic. She was also sought after to speak by churches because of her down-to-earth understandable messages.

Alice Walker originally created the name “womanist” to describe Black women’s experiences and understandings of Black liberation and Black feminism. Dr. Williams’ writings described and expanded early understandings of Womanist Theology, bringing to light the theological and cultural importance and value of Black women’s experiences and analyses.

She critiqued ways in which Black women’s experiences and insights were often ignored in Black Liberation and White Feminist Theologies of the time–as well as the larger culture. She critiqued the lack of democracy in the U.S. due to racist practices.

Dr. Williams wrote of the importance of Jesus’ life, teachings, and relational ministry as sources of salvation, rather than his death on the cross. She critiqued atonement theory, which created a stir, particularly at the 1993 Reimagining Conference, where her involvement was formative. Her theological writings and teaching challenged white supremacy, patriarchy, and western colonialism. She noted that Hagar is the only person in the Bible allowed to name God. While Hagar was pregnant and alone in the wilderness, Hagar named God, the God who sees me.

Dr. Williams was a contributing editor to Christianity and Crisis. She authored many articles, book chapters, and poems.

Dr. Williams trained in community organizing during her teaching days at Union. She worked with Harlem Initiatives Together. It was a chapter in a network of local community-based and faith organizations called the Industrial Areas Foundation. This was the largest such network in the U.S. Dr. Williams was a keen listener wherever she was. She listened deeply to women’s experiences, and in this role, she listened to her neighbors struggling with poverty. She was sought after to preach at churches and generous with her time. She also taught others to set limits by saying no at times and not accepting every request. During this time she joined and taught children’s Sunday School at Harlem’s St. James Presbyterian Church.

Dr. Williams is remembered for her quote, “All women regardless of race or class have developed survival strategies that have helped [them to] arrive sane at [their] present social and cultural locations.” This 1985 quote from a Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion article concludes as Dr. Williams says that it is important for “feminist-womanist-mujerista and Asian women” to “remember, commemorate, and lift up for ourselves and subsequent generations of women the resistance events and ideas.”